In-process Gauging Could Increase The Profitability Of Your Old Grinder

When it comes to the machining process, efficiency is a recurrent topic in the workshop, trade journals and at exhibitions. Many technology providers in the machine tool industry are constantly investing to help the optimisation of the machining processes, and every year there is always something new to look at. However, these technological ‘advances’ are sometimes minimal with a questionable return on investment (ROI). Here, we talk about one of the most effective ways to increase the profitability of your machine with Francesco D’Alessandro, a business manager with over two decades of experience in industrial equipment with a specific focus on spindle monitoring systems for machine tools, and process control systems for grinders.

“Grinding is often one of the last steps of the machining process for a large variety of workpieces. In fact, by the time a production part reaches a grinding machine, generally speaking, that part has already been subject to significant machining – and added value. A workpiece that goes to a cylindrical grinder, for instance, likely has previously spent time on a lathe and on a machining centre too. If something should happen during the grinding process that results in the part being scrapped, then the entirety of that machining investment, the turning and the milling, plus any time spent grinding, is lost. Consequently, a critical requirement of grinding is to safeguard the value that has already been added to the part.”

This is how Francesco starts the discussion, by looking at the big picture of a typical journey of a part in the metal cutting sector. Being a former mechanical design engineer for 13 years before transitioning into business development roles in 2012, he provides us with a unique, down-to-earth view on just how high the stakes are in today’s grinding processes. The manufacturers of machines know this trend very well when delivering new equipment. However, although many legacy machines with 20 plus years of operation are still running and are in good shape, they might not be able to deliver the new key performance indicators (KPI). With that being said, the present fundamental challenging question is not only how to retain high production rates no matter what, but by what means can we optimise the grinding process in current machines so that useful seconds per part may be gained, without compromising the quality.

“In grinding, small details can have a huge impact on the overall performance of the machining process, whether we are talking about cycle time, dimensional tolerance, or roughness of parts. Everything depends on microns, which in turn rely on both the machine and the operators,” Francesco states. “There are processes where technology can help and others where they depend solely on manual operations. The latter is open to mistakes being made, and here there is a compelling case for installing an in-process gauging system.”

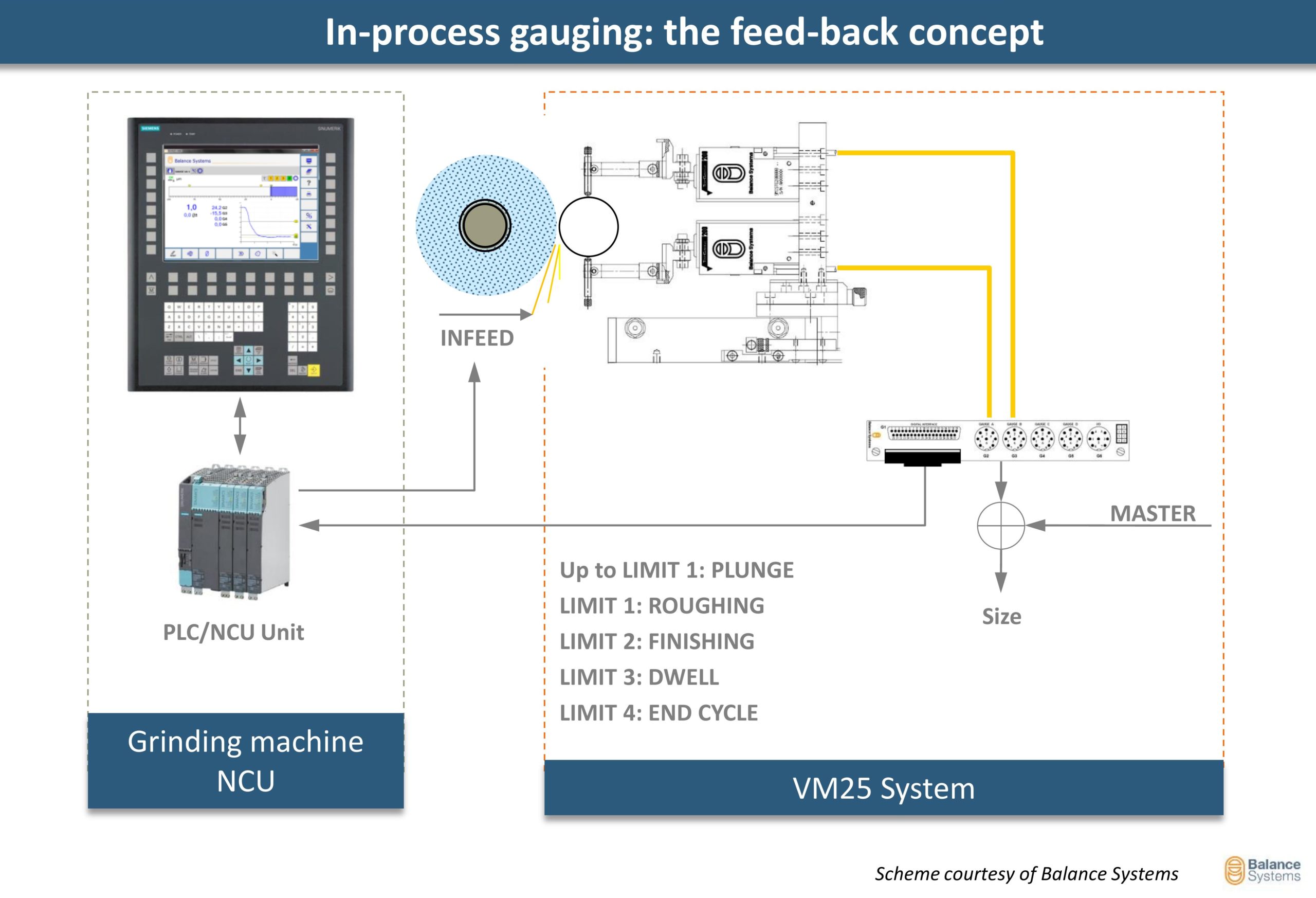

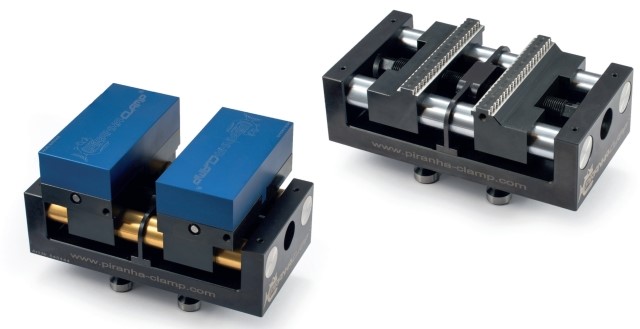

In-process gauging is an ancillary system that can measure the part whilst being ground and, in real-time, automatically control the in-feed of the grinding wheel so that every part produced by the machine is within tolerance according to the manufacturing specifications. It provides a 100% production check that even compensates the wear of the grinding wheel automatically. Due to the harshness of the grinding process, the gauging operation is performed with the gauge’s fingers in physical contact with the workpiece; the only way to get a reliable diameter measurement in these hostile conditions. Over the decades, this solution has become more robust and a few vendors are recognised as having reliable systems, one being Balance Systems.

The cycle time for a mid-size part on regular OD manual grinders can be around three to six minutes. In these types of machines, the dimensional accuracy of the parts is subject to human error because the operator has to measure the diameter of the workpiece, calculate the residual stock, and then proceed with the next machining step. In order to reduce the risk of scrapping any parts, operators tend to be conservative and remove less material than necessary; this establishes a vicious loop that increases the cycle time and as a consequence, labour costs for the employer. Using in-process gauging, this process is carried out automatically by the machine, with an evident reduction in cycle times and ramp-up of production volumes.

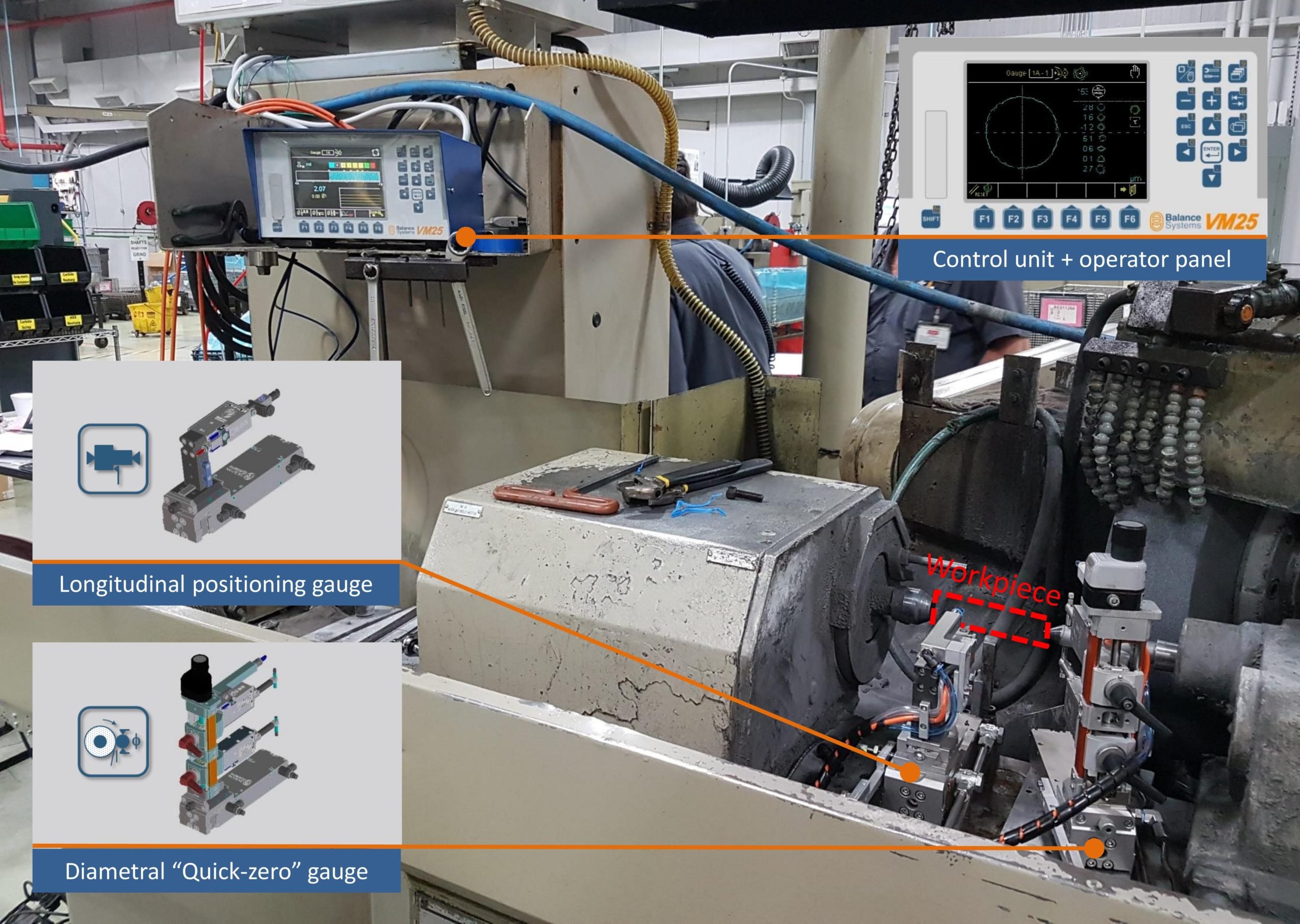

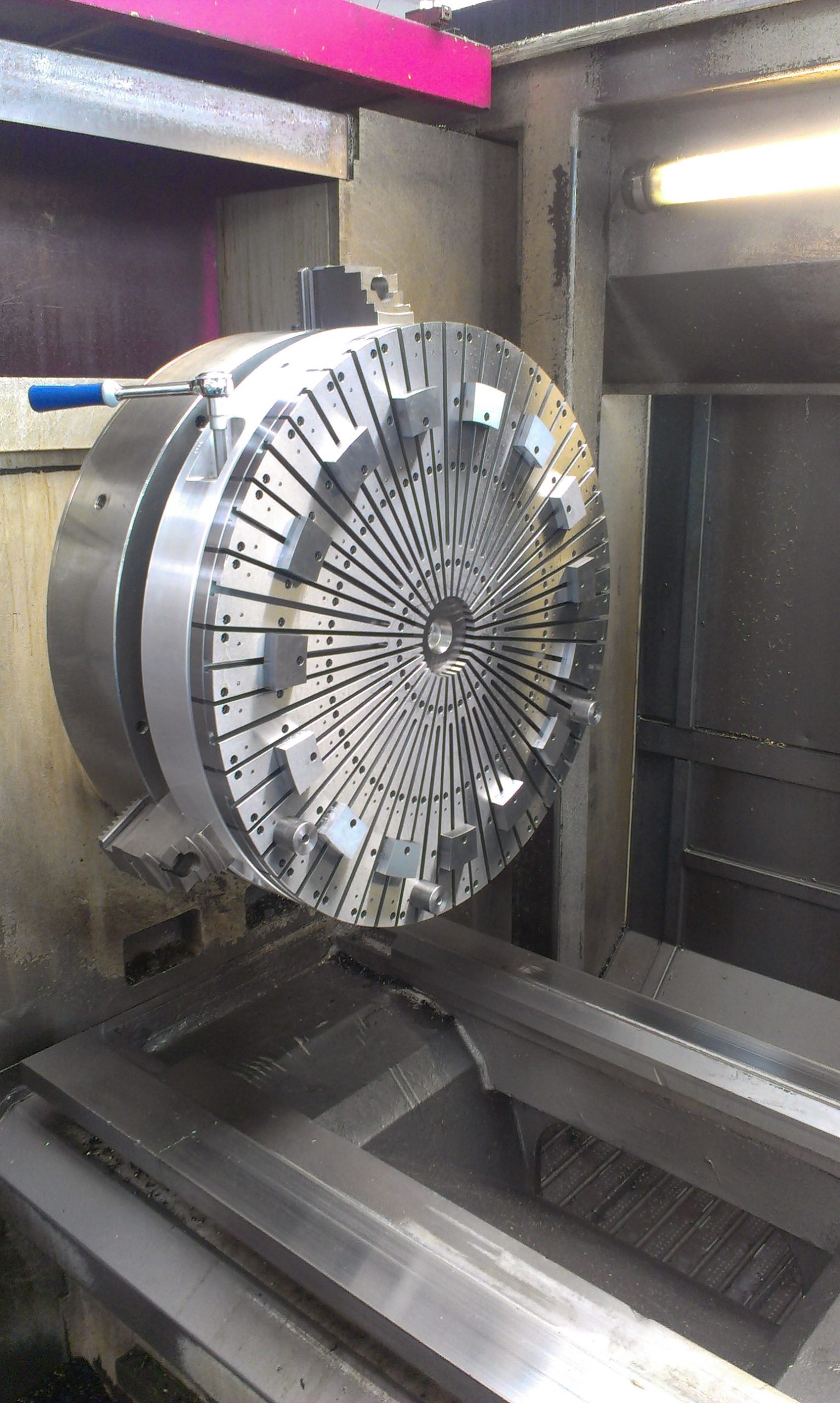

“The investment for these systems starts at around £4,500, up to tens of thousands, depending on the complexity of the part and the level of automation. My team in the UK and I are getting more interest for these solutions every year, especially from legacy machine tool users. Just to give you an idea, we recently turned an almost 30-year-old machine into a semi-automated solution capable of a 60 second cycle time [picture below]. We used a VM25 amplifier with diametral-axial flagging system TG200, all designed and manufactured by Balance Systems. The ballpark investment was around £15,000 and with the benefit in terms of productivity it was an easy decision, especially from a financial standpoint. With this system, it is also possible to conduct shape analysis of every part without removing it from the machine.”

Of course, with every improvement there is always a price to pay. Besides the initial investment to source and install the equipment, there are other hidden costs to take into consideration. For example, training of the personnel to correctly use the equipment, which includes: how to handle the change-over between different production batches, the periodic cleaning of the gauges, and also the handling of unpredictable (and hopefully rare) system crashes, that typically happen during the loading/unloading of the parts or due to incorrect interpolation of the axes.

“The implementation of a gauging system like this, in my experience poses a challenge for both sides. The end-user has to adapt the internal SOP [Standard Operating Procedure] with the new requirements of the gauges. All machinists and maintenance staff need to be informed and trained about the new equipment, how to operate and care for it.

“On the other hand, the challenge for those who want to install an in-process gauging system is the integration of the signals into the machine tool. There can be a broad range of technological ‘hurdles’ to overcome in the field. So, I would strongly recommend to any business to only use experts with a proven track record in these applications. For any questions, feel free to call our team in the UK on 01827 700000.”

It is important to note that in-process gauging systems cannot be installed on every type of grinding machine. For example, centreless and double-disc machines have obvious limitations due to their machining concept, making it very difficult (in some cases impossible) to locate an external element, such as the gauges, in contact with the part while it is machined. However, Francesco tells us that there are solutions called ‘pre-process’ and ‘post-process’ gauging systems that allow automating the grinding cycle even on these machines, and so reaching the new challenging KPIs of today’s manufacturing world.

Looking at the numbers it is clear to see how it would be worth the investment to implement this solution. A 6-minute versus 1-minute cycle time, without and with in-process gauging respectively, is a very powerful comparison. Whether you need to produce mid-size batches or extended run volumes, the ROI of an in-process gauging system is compelling. What could your business do with six times the production capacity?

www.balancesystems.com