Volumes edge up in auto sector smashed by Covid and chip shortages

Volumes edge up in auto sector smashed by Covid and chip shortages

Automotive manufacturing in the UK is changing radically. Volumes are down for the fifth year straight but semiconductor shortages are easing and units in 2023 are expected to rise. Electric vehicles are rising fast, but supply chain blocks, high energy costs, business rates and skilled employee shortages all threaten the sector. Will Stirling reports.

At first glance, the UK car and vehicle industry looks much the same as it has for years. There are five global mainstream car makers in Britain, down from six: Jaguar Land Rover (JLR), MINI, Nissan, Toyota and Vauxhall. Honda’s final official day of car production was 30 July 2021. Engines are still manufactured by Ford in Dagenham, by Toyota in Deeside, by JLR in Wolverhampton and others – the UK has lost one engine manufacturer since 2019. Bus, van and truck domestic production all have largely the same footprint as 10 or more years ago.

What has changed is that volumes are down heavily and remain, for now, on a falling trend. There are some signs of recovery as key component shortages ease. Electric vehicle production is rising. There is more pressure on car companies than ever to change – to decarbonise but to manage intense change like inflation, component supply shortages and energy prices. Vans, or light commercial vehicles (LCVs), are the only segment to grow consistently in recent years. LCVs on the road has increased by 29%, to 4,604,861 units on the road in 2020, largely driven by growth in the construction industry, says the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT). While as a trend commercial vehicle (CV) production is falling, the CV segment had its best six months in a decade, production growing over 64% in June.

What has changed is that volumes are down heavily and remain, for now, on a falling trend. There are some signs of recovery as key component shortages ease. Electric vehicle production is rising. There is more pressure on car companies than ever to change – to decarbonise but to manage intense change like inflation, component supply shortages and energy prices. Vans, or light commercial vehicles (LCVs), are the only segment to grow consistently in recent years. LCVs on the road has increased by 29%, to 4,604,861 units on the road in 2020, largely driven by growth in the construction industry, says the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT). While as a trend commercial vehicle (CV) production is falling, the CV segment had its best six months in a decade, production growing over 64% in June.

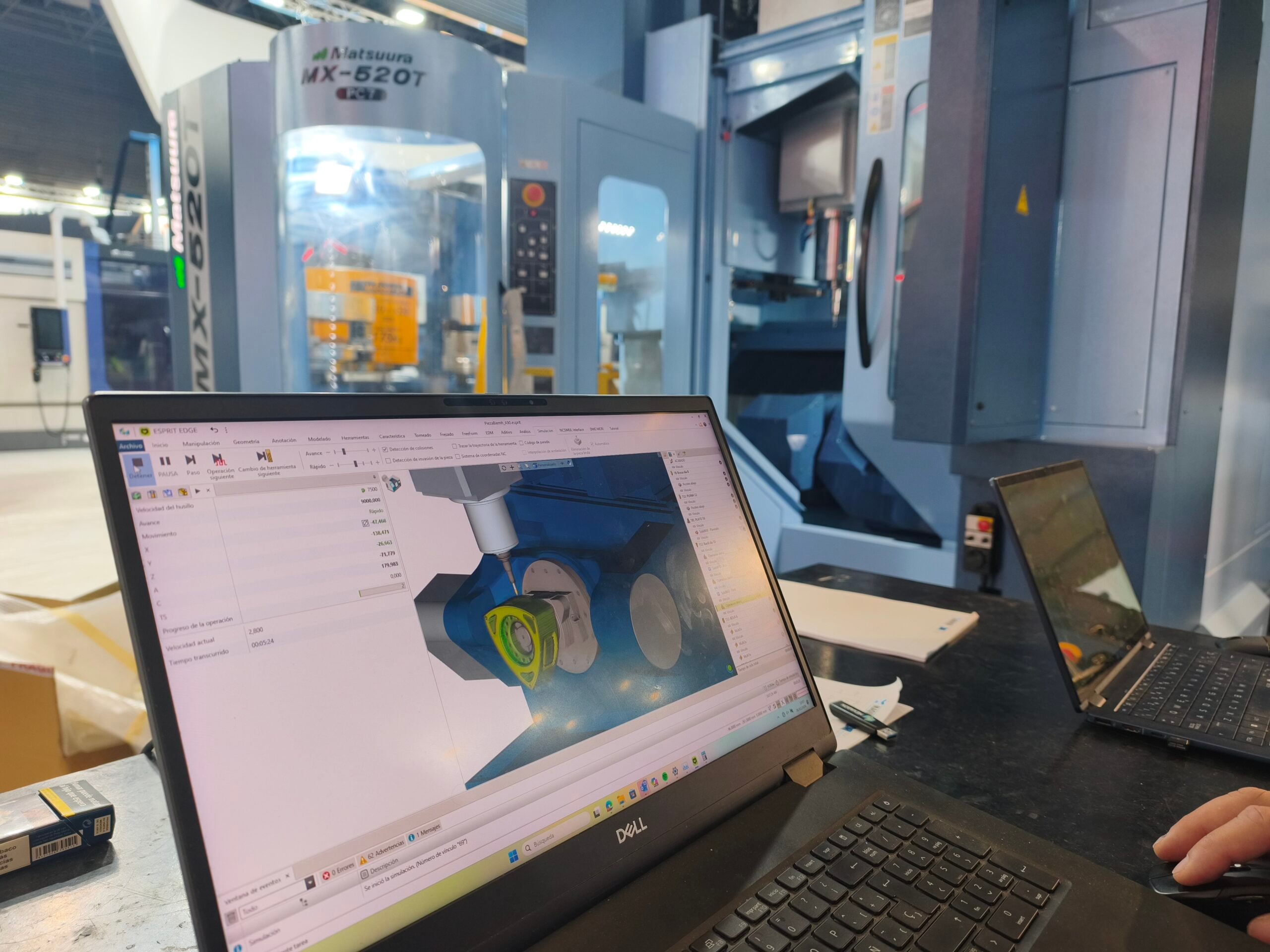

It’s common knowledge that a big reason for low car production is semiconductor shortages. Semiconductor, or chip manufacture is confined to a few, very large specialist factories in Taiwan and one or two other places, and supply was hit hard by Covid. Other factors include the impact of the Ukraine war, lockdowns in China, structural changes in the sector, inflation, energy costs and the shortage of other critical parts. But this bottleneck shows signs of relief. June was the second consecutive month in which the UK car industry grew, up 5.6% with 72,946 car units built, and this was largely due to an easing in semiconductor supply.

Half-year health check: Despite this UK car production declined -19.2% in the first six months of the year, according to SMMT figures published in late July, with 95,792 fewer vehicles built compared with the same period in 2021. The group said from January to June 403,131 units were built, “representing the weakest first half since the pandemic-ravaged 2020 and worse than 2009 when the global financial crisis decimated demand.” The closure of Honda’s Swindon plant in 2021 will have had a big effect on total units, too. The output of hybrid, petrol and diesel cars declined, by -19.9%, -8.0% and -60.2% respectively in the first half of the year.

In May, monthly engine production increased 12.3%, the first growth since June 2021.

Jobs, suppliers and other metrics

Jobs, suppliers and other metrics

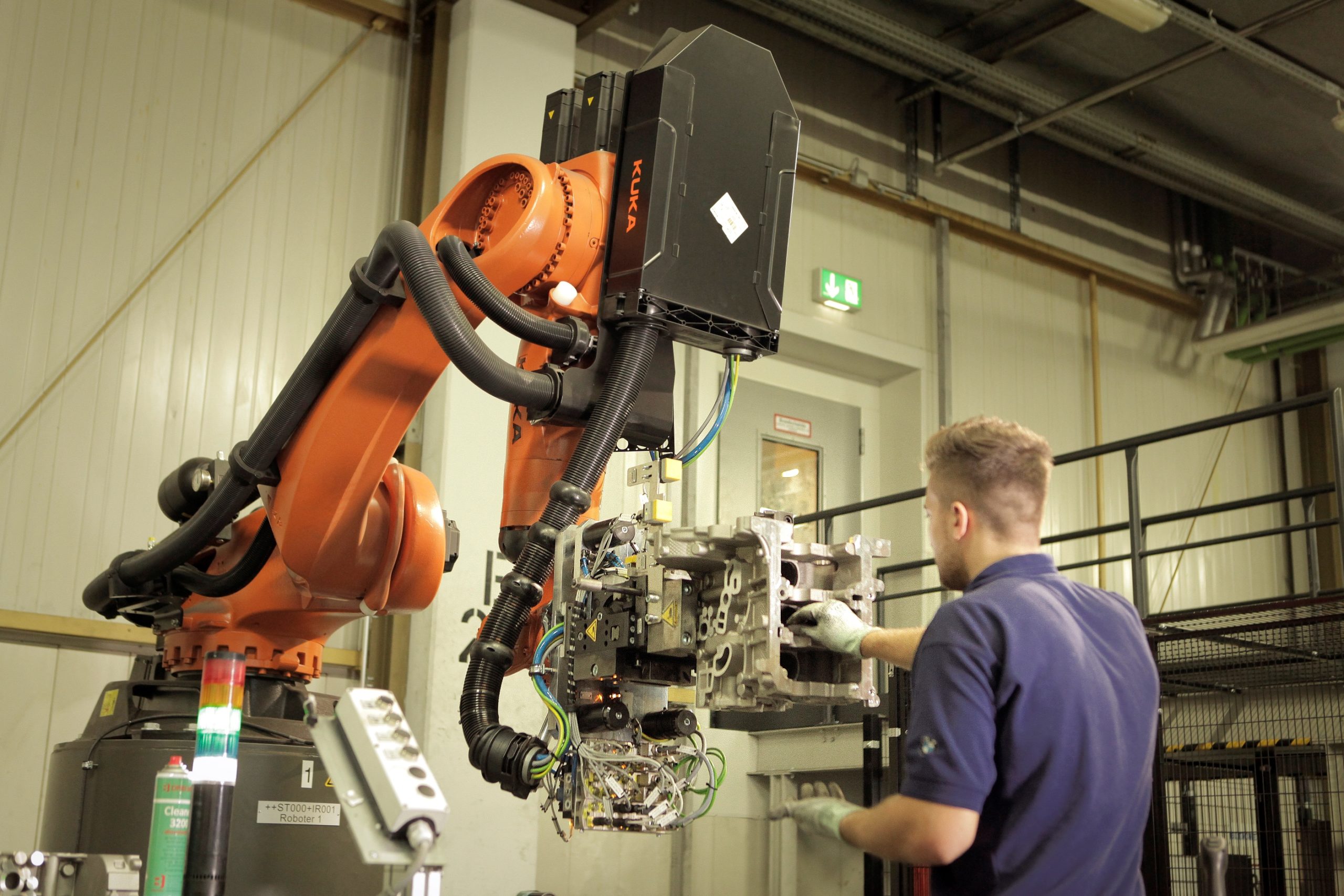

A concerning figure is jobs. Employment in all areas of UK automotive fell to 781,800 in 2021, a loss of 41,200 jobs in two years. This spanned the Covid pandemic, but it is still a big fall – 5% of all jobs. Like the airline and other industries, after layoffs when production increases – as it is expected to, by 2023/24 to over one million vehicles per year – jobs will return but will the industry struggle to find skilled automotive fitters and engineers who have moved on? It’s a cyclical problem, which seems to be partly solved in Europe’s biggest automotive market, Germany, by Kurzarbeit, or short-time work insurance, that subsidises worker payments in a downturn. It’s a system that has never been adopted in the UK, where agency workers and rapid rehiring programmes seem to plug the gap.

The ‘real’ health of UK automotive can only be ascertained when the efficient supply of parts and the effects of the Ukraine crisis have both normalised. By then, as the 2030 deadline for ceasing the manufacture of non-hybrid/non-electric cars approaches, ICE vehicle production will likely fall again as car makers begin to mass produce electric models.

Electric vehicles

The production of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) has proven to be a bright spot for the sector, with 32,282 produced in the first half of 2022, a growth of 6.5% on 2021. This was boosted by a whopping 44.2% rise in June, making a record output of zero-emission vehicles for the month. This was in part due to £3.4bn of new investment (government and private sector) committed to the UK’s zero emissions in automotive in the year’s first six months.

It’s no surprise that electric, hybrid-electric and hydrogen-electric is the segment with the newest entrants. In recent years and months Arrival, Tevva, Switch Mobility, EV Technology Group, and Maeving for motorcycles have formed a growing list of new electric vehicle manufacturing companies. They join London Electric Vehicle, Wrightbus and other more established low or zero-emission manufacturers.

River Simple is a growing UK-based hydrogen fuel cell eco-car company, bucking the trend of electric powertrains and choosing a fuel cell platform. In June electric and hydrogen truck company, Tevva made history by launching the first hydrogen fuel cell-supported electric heavy goods vehicle to be manufactured, designed and mass-produced in the UK. The Tilbury-based company already had a full-battery electric HGV in production.

River Simple is a growing UK-based hydrogen fuel cell eco-car company, bucking the trend of electric powertrains and choosing a fuel cell platform. In June electric and hydrogen truck company, Tevva made history by launching the first hydrogen fuel cell-supported electric heavy goods vehicle to be manufactured, designed and mass-produced in the UK. The Tilbury-based company already had a full-battery electric HGV in production.

EV makers’ main challenge is to move from the proving stage to volume manufacture – the most difficult stage in any car company’s genesis. Electric-van and bus maker Arrival received EU certification and European Whole Vehicle Type Approval in June, an essential step for starting trials with customers in Europe. It is under some stakeholder pressure to produce its first production vehicles. Mainstream production was expected to first come out of its North Carolina, US facility and then its Bicester, UK site. It is expected to produce the first vans from Bicester, near Oxford in autumn 2022 and shareholders, suppliers and Arrival itself are eager to reach this milestone.

Create a competitive environment to build vehicles

Tough conditions including high inflation and sky-high energy costs are passed down to suppliers at all levels. Equipment and robotics suppliers talk of razor-sharp margins in automotive in 2022, making big projects hard to price and make money on. Analysis by SMMT in June showed that UK auto manufacturers face a £90 million increase in energy bills this year as costs surge 50% – a figure that may rise come the autumn. This sector already spends £50m more per year for energy than its EU counterparts, in Germany, France and Italy, with the UK having some of the highest electricity costs in Europe.

If policymakers are to limit the decline in car production and help accelerate the recovery, they must bring inflation under control, and provide carmakers with energy cost relief or subsidy, after the sector has endured what SMMT Chief Executive Mike Hawes says has been a ‘long Covid’. “From Covid impacts to component shortages, supply chain disruption to trade uncertainty, and regulatory change to rising inflation, the challenges facing this sector are immense,” he said. “Nevertheless, addressing the UK’s high energy costs is the industry’s number one ask.”

“Help with energy costs now will help keep us competitive and be a windfall for the sector, stimulating investment in innovation, R&D, and training – all reinvested in the UK economy. With the right backing, this sector can drive the transition to net zero, supporting jobs and growth across the UK and exports across the globe.”

And don’t ignore the vital future role of connected and autonomous vehicles (CAVs) to the UK economy. We can’t see driverless cars yet, or very few, but the CAV market is expected to be worth >£62bn by 2030 and provide +420,000 new jobs, let alone improvements in safety and accident prevention.